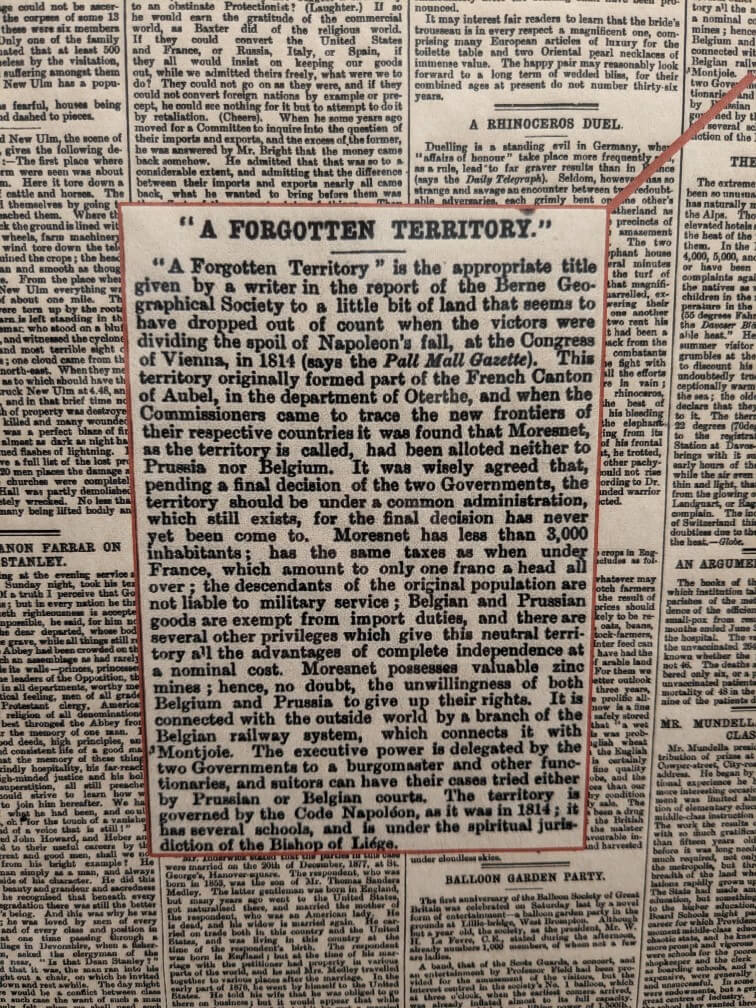

I wonder if you’ve ever heard of Neutral Moresnet, a peculiar slice of land in East Belgium, which was once its own independent entity? I hadn’t until only recently. And it was even later that I thought about going to visit the site – to find out there are still some scant traces of the former historic oddity left to visit.

I’m not even sure when I first learned of its existence, but I was pretty captivated (read: I fell instantly into a Wikipedia rabbit-hole) – how could a tiny country have existed practically on my doorstep that I’d never heard of?

So for anyone thinking of visiting the land that was once known as Neutral Moresnet in a (literal) slice of land wedged up against the German border, this blog post is for you. But first let’s tackle the big question: what the hell was Neutral Moresnet?

What was Neutral Moresnet?

Neutral Moresnet was an area of land that was under special jurisdiction for 103 years, from 1816 – 1919. But it seems as though the question ‘what is Neutral Moresnet?‘ would have been just as valid during this period as it is today: the area was never officially recognised as independent; Belgium acted as though the area was part of Belgium and Prussia acted as though the area was Prussian, but it very specifically belonged to neither.

A note on terminology: Wikipedia uses the term condominium (which is the most accurate) but the term I have seen most commonly used to refer the area is former microstate (which I personally prefer – read on to find out why) so I use the two fairly interchangably for user experience reasons.

So why did Neutral Moresnet come to exist? The simple answer is: a very profitable mine.

The history of Neutral Moresnet

Why was Neutral Moresnet created?

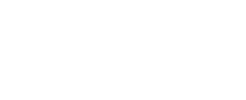

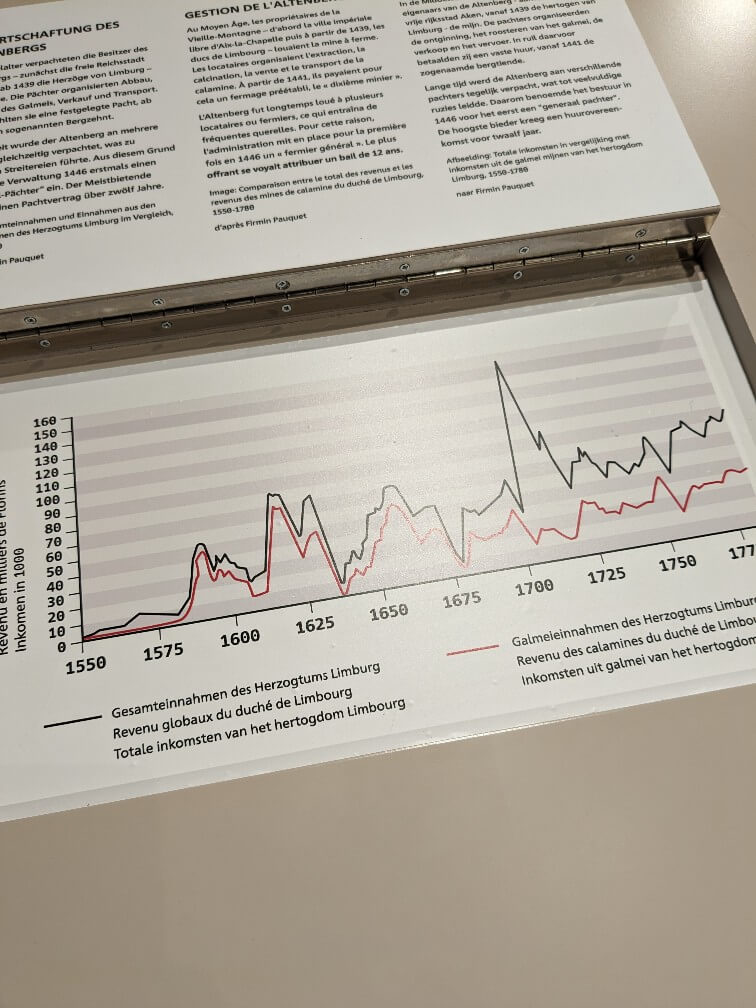

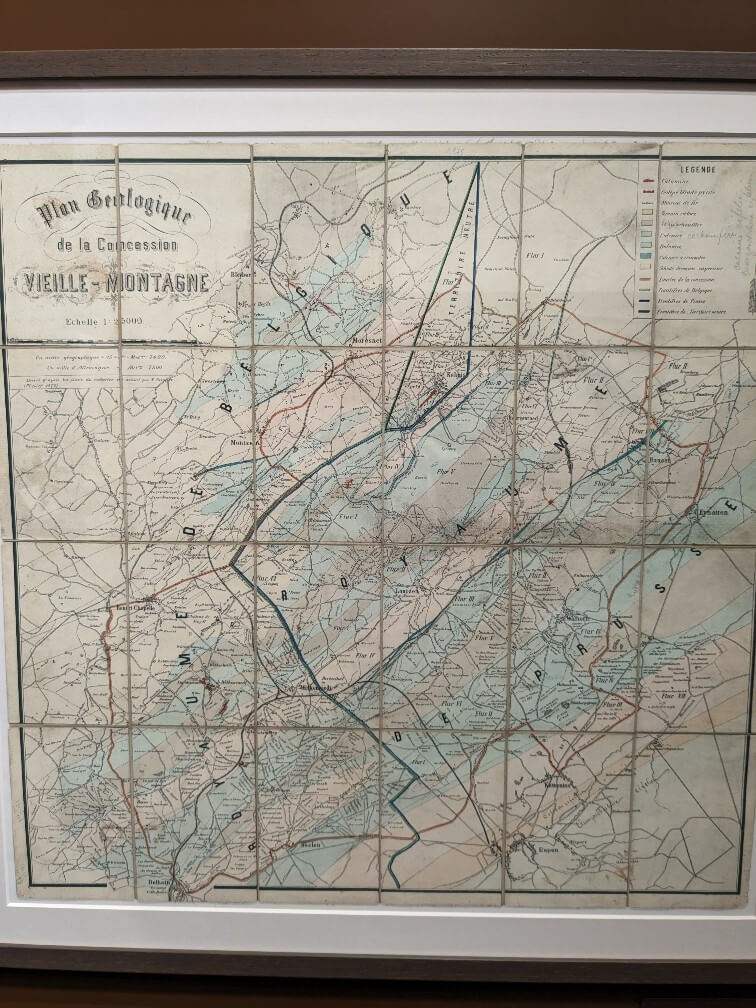

The site of Neutral Moresnet was historically home to a calamine mine. The area had been prized for centuries, often changing hands between regional powers and, even earlier than that, rival cities or duchies. The area once belonged to Aix-la-Chapelle, for example – known as Aachen today.

In the early 19th Century, the Great European powers had a series of conferences aimed at re-drawing the borders of Europe, the most famous being the Congress of Vienna 1814-1815. This meant that the mine was once again seemingly up for grabs and the Kingdom of the Netherlands (later Belgium) and Prussia (later Germany) were both determined to take the mine for themselves.

How was Neutral Moresnet founded?

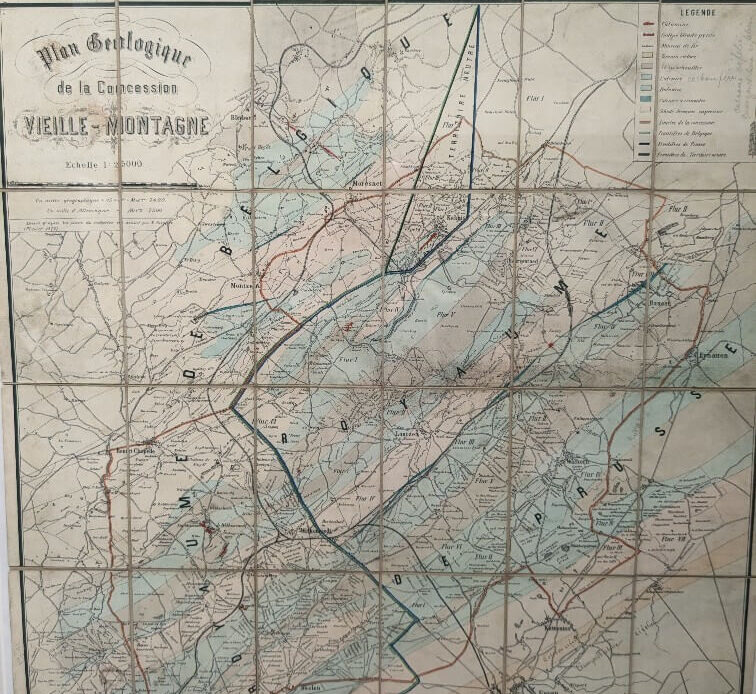

After a series of such conferences, the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Prussia had still not reached a conclusion about the small piece of land sitting on their shared border. And so a temporary solution was suggested that the lands either side of the mine would be ceded to Prussia and the Netherlands respectively, and a narrow almost-triangular strip of land (including the mine) would become a neutral territory, administered jointly, but with both armies forbidden from entering.

The borders were officially demarcated and so Neutral Moresnet was officially created.

Life in Neutral Moresnet

I think it’s safe to assume that life in the microstate was good. On the creation of Neutral Moresnet, it was said to be home to 50 houses and 400 people, but 100 years later, the same area was home to 4,000 people.

Residents enjoyed certain perks as a result of the situation: the original 400 occupants and their descendants were officially given the nationality of “Neutrals” in their passports and were exempt from military service. (This originally applied to anyone in the territory but this was revoked after so many people moved there to avoid military service.)

The microstate was also a taxation loophole, as both neighbouring countries viewed it as belonging to them and only applied domestic taxes. Therefore taxes were low for locals, but the area naturally became a smuggling hotspot. Similarly, other loopholes were exploited: once gambling was outlawed in Belgium, a casino was opened almost instantly in Neutral Moresnet.

There was even a common phrase in use at the time: “Belgien vielleicht. Preußen nimmer. Neutral immer.” It means: “Belgium maybe. Prussia never. Neutral always.”

I read this on a sign at the museum.

Neutral Moresnet recognition

One thing I was really surprised to learn was that the mine deposits were pretty much exhausted by 1884. Imagine being so adamant about controlling a mine that you accidently create a new quasi-country, only for the mine to be completely depleted less than 70 years later…

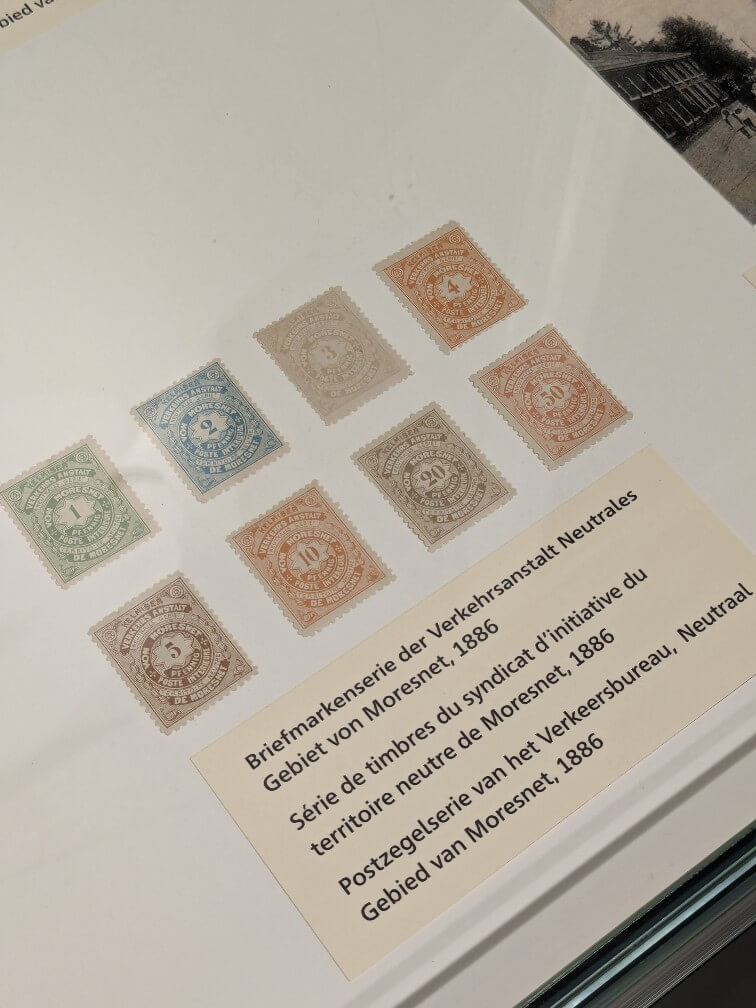

It was around this time that local people began to push for more permanent recognition of Neutral Moresnet. This involved attempts at creating their own currency and postal regime, which were both thwarted – mostly by Belgium.

That’s one of the reasons I prefer the term “microstate” to condominium, as there is a lot of evidence to suggest that the people of Neutral Moresnet did really want to preserve their unique status and even push for independence.

There was even a common phrase in use at the time: “Belgien vielleicht. Preußen nimmer. Neutral immer.” It means: “Belgium maybe. Prussia never. Neutral always.”

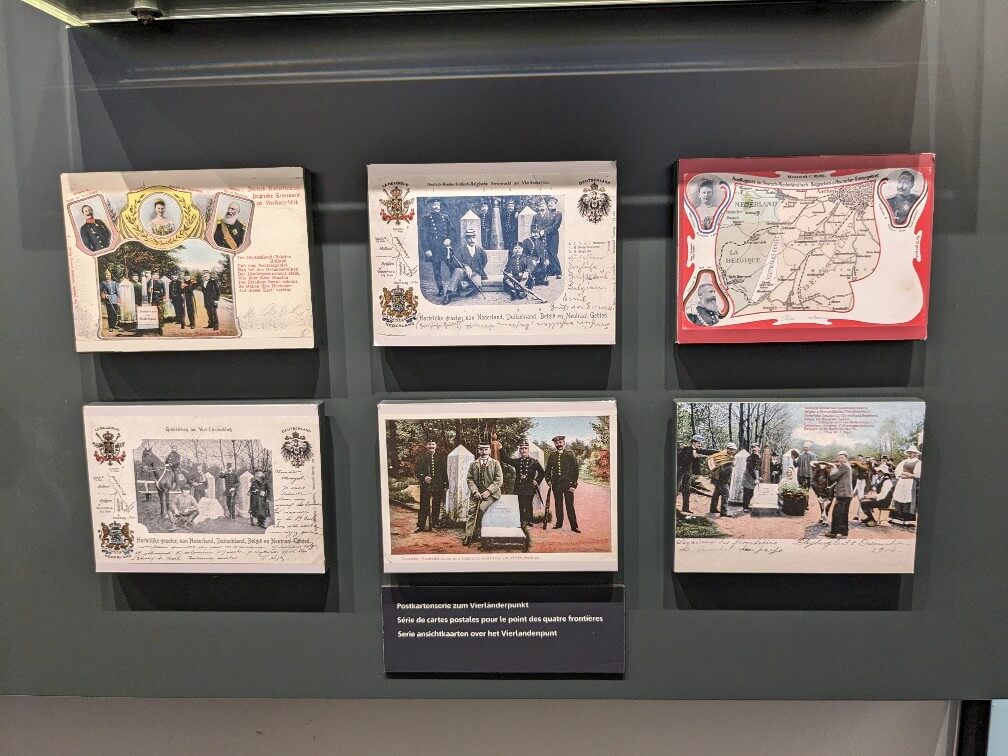

Interestingly, the legacy of Neutral Moresnet is particularly well-captured in postcards from the time, particularly those related to the Vierländereck (four-country corner) located at the extreme north of the territory. I guess this goes to show that even at the time, the condominium was viewed as a novelty and not necessarily taken seriously.

The home of Esperanto?

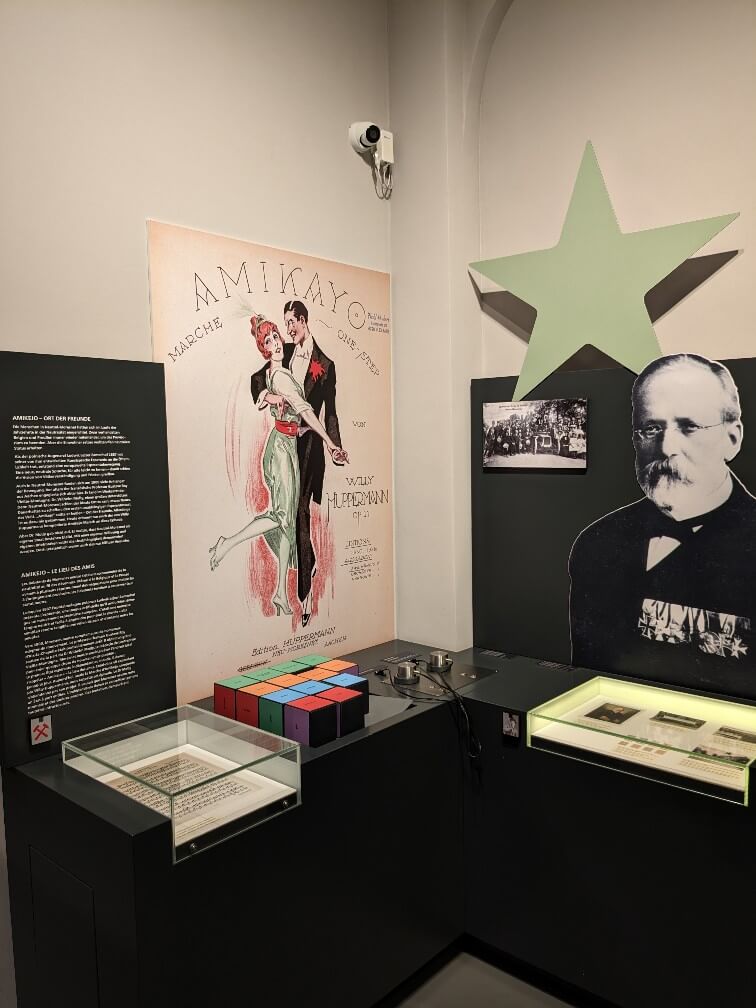

One incredibly bizarre manifestation of this hope for independence was the idea to remodel the microstate as the world’s first Esperanto-speaking country.

The idea was pushed from 1908 by a man named Dr. Wilhelm Molly, who passionately campaign for Neutral Moresnet’s independence. He proposed renaming the state Amikejo, meaning ‘place of friendship’ in Esperanto. Surprisingly, the idea did actually get some traction, with a national anthem being written in Esperanto and the World Congress of Esperanto even naming Neutral Moresnet / Amikejo the world capital of Esperanto (although they never once held their regular congress there…).

But unfortunately it didn’t do anything to help safeguard a future for the territory.

Why was Neutral Moresnet abolished?

The microstate of Neutral Moresnet was effectively abolished at the start of WWI when Germany invaded Belgium in 1914. Germany then annexed the region during the war, but in the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Belgium was given full control of the area. And so Neutral Moresnet officially ceased to exist, 103 years after its creation.

Visting Neutral Moresnet and Ost-Belgien

How to visit Neutral Moresnet today

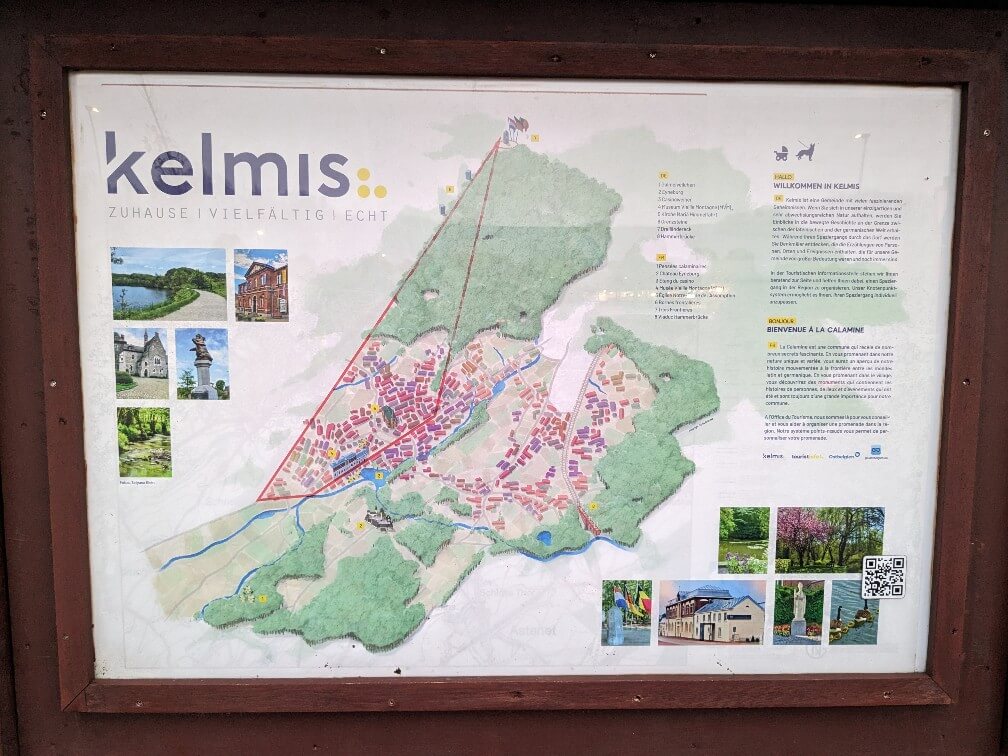

Today the land of Neutral Moresnet is known as Kelmis (the German word for calamine), a town of 11,000 people situated in the German-speaking community of Belgium (which has recently rebranded as Ost-Belgien or East Belgium). It’s a really unassuming town honestly and it’s hard to believe that it has such an interesting history.

But there are still plenty of remnants of Neutral Moresnet’s history. In fact, 50 of the original 60 border markers are said to still exist and I found these two excellent Dutch blogs (On the Border and Grenspalen.nl) by enthusiasts on a mission to find them all. Handily two are situated on the main road through the town. (Marker 01, Marker 60)

You’ll also find a few more subtle nods to the town’s past here and there, including the flying of the black-white-blue Moresnet flag.

Museum Vieille Montagne / Altberg – the Neutral Moresnet Museum

Of course, the real showstopper for anyone interested in the history of Neutral Moresnet is the Museum Altberg / Vieille Montagne (website German or French only), which has a fantastic permanent exhibition on the history of Neutral Moresnet. The exhibits are interesting and interactive and there is a fantastic complimentary audio guide, which features both factual and anecdotal information. Much of what I’ve discussed in this post I learned at the museum.

The building itself was built by the administration of the Vieille Montagne mining company and is itself a beautiful building to visit. One highlight of the museum for me was a table cut in the shape of the territory itself. The gift shop is also great.

Other border sights in East Belgium

Eupen and Ost Belgien

On our daytrip to Kelmis back in January 2024, we also took in some other nearby sites. And interestingly, this area has a few other curiosities remaining from the frequent border changes in this area – a remnant of the fact that this wider area has historically been where the different Sprachraums of French and German meet – and still is today.

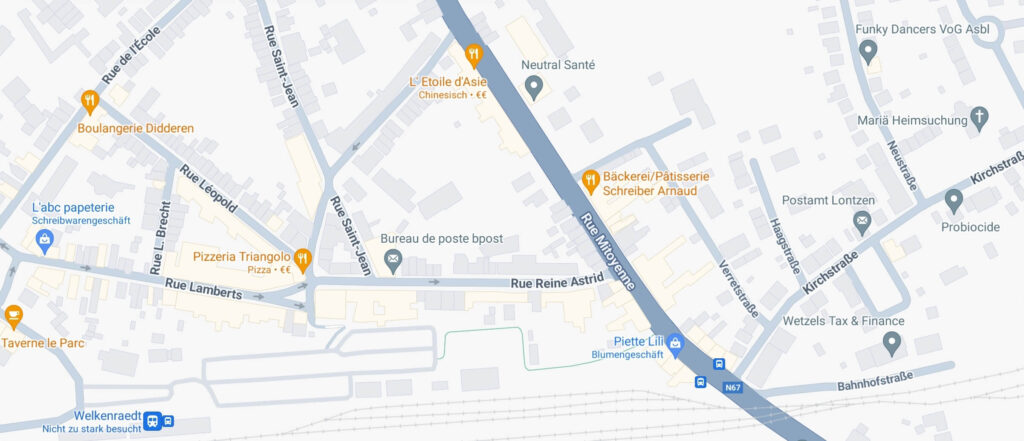

Firstly, several old Prussian-Belgian border markers can still be seen along the road which is also the former border between the two states. Interestingly enough, this road still does form a border of sorts – between the Francophone and German-speaking communities in Belgium. In fact, I noticed on my friend’s SatNav that all the roads to the East of us had German names and the West, they were all French – something you can see on Google maps.

We stopped for lunch in Eupen, the capital of Belgium’s German-speaking community. And it really didn’t feel like we’d left Germany – all shop signage was in German, we heard German being spoken almost exclusively, and apart from it being very, very hilly, it felt like we could still be in the Rheinland.

I was looking forward to asking someone how locals felt in relation to Germany, considering how close they are to the border and sharing a common language. Unfortunately at lunch, our waitress was the only French speaker we met who didn’t speak any German. Instead I asked the girl in the ticket office at the museum who it turns out actually was German and had moved to Belgium. But still, her feeling was that locals felt very proud to be Belgians but nevertheless had a strong connection to Germany, particularly Aachen being their closest big city.

The Vennbahn and more Belgian border quirks

This area is also home to one of the most famous border oddities in Europe – the former Vennbahn railway, which forms a thin slice of Belgium, which cuts through otherwise German territory. I’ve visited the Vennbahn previously, but I haven’t written about it (yet…), so instead I’d recommend you check out this video from one of my favourite YouTubers, The Tim Traveller.

Belgium has some weird and wonderful borders. And most countries might think that a former semi-independent condominium and a former railway line in a neighbouring country might be enough quirks, Belgium has at least one more fantastic ace up its sleeve: Baarle-Hertog. You can read more in my post below (and trust me, if you enjoyed this post, you’ll love this one too!)

Read about more bizarre Belgium borders: the curious case of Baarle-Hertog and Baarle-Nassau.

I hope you enjoyed this post and I hope you are equally intrigued by this overlooked part of European history!